Join 8,000 Iceland Travel Fans & Unlock Exclusive Discounts

Subscribe and instantly receive free discount codes for tours, car rentals, camper vans, and outdoor gear — carefully hand-picked to help you save on your Iceland adventure.

- ✔ Instant access to exclusive discount codes

- ✔ Savings on tours, car and camper rentals

- ✔ Tips and inspiration for planning your Iceland trip

Nine years ago, I bought myself a book before Christmas. It was the debut of a new author, Sigríður Hagalín Björnsdótir, who at the time was a journalist at the Icelandic National Television. The book was called ‘Eyland’ – a literal translation could be ‘Island Nation.’ I remember starting to read it on Christmas day and I was completely blown away by this tour de force of an apocalyptic dystopia. In the book, Iceland is mysteriously cut off from the rest of the world. Sigríður takes this situation relentlessly, without any mercy to the reader, to its inevitable, dreadful conclusion. I read it in one sitting, and I have never dared to read it again. I am somewhat anxious to have learned that it will be made into a film!

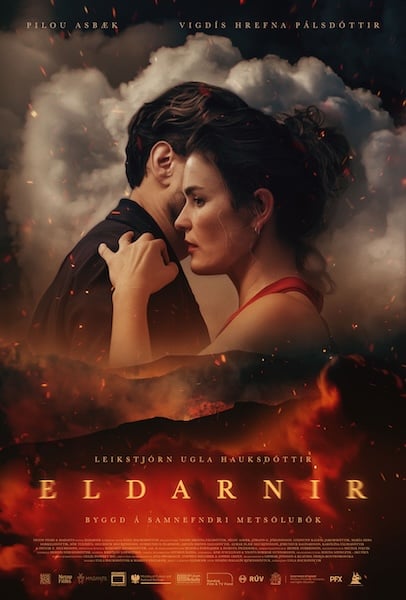

Since then, Sigríður has published five more novels. ‘Eldarnir’ and ‘The Fires’ became sensations in Iceland and have also found success in markets from Germany to the United States. ‘The Fires’ describes a scenario in which a major volcanic eruption occurs near Reykjavik. That is not nice for anyone, as readers will discover. The book has been turned into a highly successful film directed by rising star Ugla Hauksdóttir. It is like other books by Sigríður: a crisp and unflinching study of human nature.

Her other books are all top-quality; she wrote about our strange new world, dominated by AI, in ‘Deus’. ‘The holy word’ is about escape and the human mind. I just finished ‘The Way of the World’, which is the prequel to ‘Happiness of this World.’ In those historical novels, Sigríður writes about Icelandic power politics of Iceland in the 15th century. This period is somewhat of a black hole in Icelandic history. This is a pity. In this period, foreign powers, merchants, the Catholic church, and the Icelandic upper classes vied for the wealth of Icelandic trade and resources. All we can tell from the fragments that remain from this period is that these players were unscrupulous and ruthless. In these novels, Sigríður does what she does best: she delivers a highly plausible and atmospheric story that makes you feel you are right in the middle of the fray.

Book a hotel and a flight to Iceland

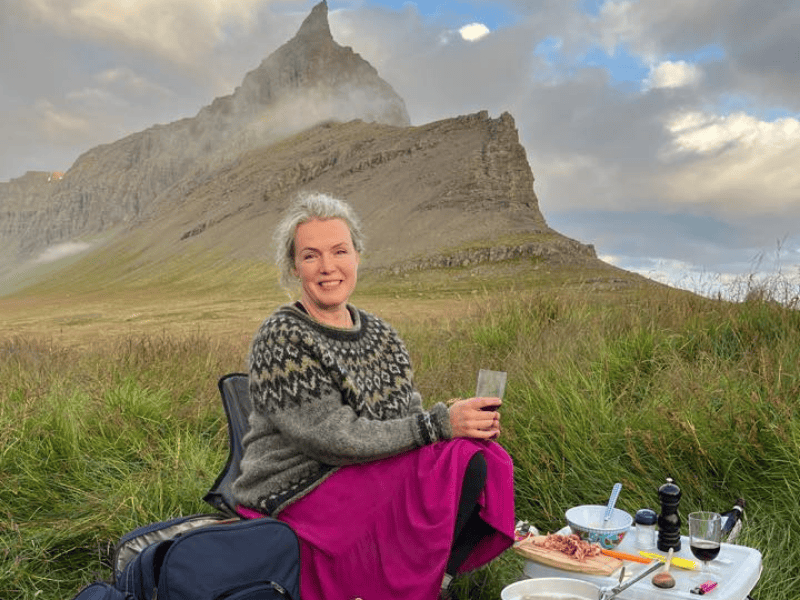

Born into one of Iceland’s notable literary families—her great-grandfather, Guðmundur G. Hagalín, was an author, and her great-grandmother, the acclaimed actress Sigríður Hagalín—she seemed destined for creative work. Yet her path took her through history and journalism studies in Reykjavík, Salamanca, and Columbia University before she returned to settle in Iceland’s capital.

Married to celebrated author Jón Kalman Stefánsson, Sigríður lives in Reykjavík. Her unique perspective—combining a journalist’s eye for truth with a novelist’s imagination, informed by deep historical knowledge—makes her one of Iceland’s most distinctive contemporary voices. And in case you were wondering, yes, she is my favorite Icelandic author.

Hey Sigríður, thank you for your wonderful books and for taking the time for this interview. What drew you to becoming a writer?

Thank you for having me, and for your generous introduction. I became a writer because of all the wonderful writers who came before me. I have always been a passionate reader, and I started writing and telling stories before I can remember, so everybody around me always expected me to become a writer. But as a young person, I felt that I didn’t have anything to write about – my childhood was very happy and safe, so I couldn’t write about any traumas, and I was too ignorant to write about anything else. So I studied history and became a journalist instead, telling real stories and trying to learn something about how the world works. But the writer was always there, I think, lurking in the shadows until she found the opportunity to come out. I remain divided between my two personae, the journalist and the writer, but the writer is taking up more of my time now.

“Eyland” was such a powerful debut—this relentless, unflinching vision of Iceland cut off from the world. Ten years later, how do you look back on that book? And now that it’s being adapted for film, has revisiting that dark vision changed how you see it now?

Thank you again! I’m always a little shocked when I reread parts of it – it seems very raw and rough to me now, brutal, even. But although I think I would write a very different novel today, I think its raw, desperate energy fits the subject, and I hope it still manages to describe how easy it is for a civilised democracy to slip into chaos and fascism.

I carried the idea with me for more than 15 years and always waited for someone else to write that book – it seemed such an obvious idea – but in the end I realised that the story had picked me, and that it was my job to write it. It only took me three months, and I had no control over the process; the story burst out of me like a howl.

Now I find it uncannily prescient – I wrote it before Brexit, before Trump, before Covid-19, and most of the events that have rattled our sense of security in the last few years. I’m looking forward to seeing what Ugla will do with it on screen – she’s brilliant, and we share a love for action as well as profound psychological drama.

You seem drawn to catastrophe—volcanic eruptions in “The Fires,” societal collapse in “Eyland,” the ruthless power struggles of medieval Iceland. What compels you to explore these extreme situations, and what do they reveal about human nature that quieter stories might not?

Well, you should see me in the kitchen! Catastrophes are my speciality.

But I’m a news reporter at heart, and fascinated by events that change the course of history and warp our sense of reality. If you think of ordinary people who lived – or died – to experience the Black Death or the Holocaust or the Gaza war, you have to admire how resilient and adaptive human beings can be. And events like that really expose you, the choices you make, the sacrifices you’re willing to make. Deep down inside, are you material for a cruel despot, an obedient minion, or a selfless hero? There’s no way to tell until you’re in a situation where you’re faced with difficult life-or-death choices. And it’s healthy and necessary to read books that force you to consider the choices you would make.

However, despite all the darkness and the disasters, I’m a hopeless optimist. I believe in the power of love, the inherent mercy and kindness of human beings, and that is the only thing that can save us.

The 15th century is indeed a fascinating period of Icelandic history. How do you approach writing about this period? What freedoms and challenges come with filling in those historical gaps?

Absolutely fascinating! And nobody knows a thing about that time in our history, so I could make up almost anything I wanted to.

What we do know is that the Black Death caused a great rupture in the late 14th and the beginning of the 15th century, first because it wreaked so much havoc in Europe that Iceland lost contact with Scandinavia. The ships just stopped coming, so we had sort of an Eyland situation, cut off from our king and the rest of the world. When the pandemic finally reached Iceland, it killed off almost everyone who could write, so our proud tradition of writing sagas and annals came to an end, and Iceland disappeared from the pages of history.

We know that around this time, the English came, at first to fish, but then also to trade, plunder, and even settle here. This upset the local power balance, with some people embracing the newcomers and getting rich from the trade, and others staying loyal to the king in Scandinavia. It was a very chaotic time, and one of the main players was Ólöf the wealthy, a powerful noblewoman, politician, and general, who ended up massacring the English to avenge her husband’s death, basically ending their reign in Iceland. Or rather, that’s one version of the story.

Most of it is stuff of legends, and I wanted to tell the story in my own way, filling in all the wide gaps in history and confronting the nationalistic myths about what happened. But I stuck to the few existing sources, and didn’t write anything that I knew to be wrong. Nevertheless, they still left me plenty of room to make things up.

We have a tendency to write the Middle Ages off as primitive, dirty, and cruel, but in fact, they were a fascinating period, colourful, complex, and bursting with culture and humour. I have tried to bring the colours back to life, to tell the stories of real, living people who happened to be there at the time.

‘DEUS’ tackles AI and our contemporary moment, while your medieval novels explore Iceland’s distant past. Do you find the same themes emerging whether you’re writing about the 15th century or our technological present?

Absolutely. DEUS emerged in between the two historical novels, almost like a reaction or an answer to them – tackling the same questions of truth, power, love, and our relationship with the sacred, but in a very different context. The difference between writing, or thinking, about the past and the present is that in the past, the impact of the events you write about is a known factor, but when you’re writing about the present, you don’t know whether the world is still standing when the story ends.

The reason I wrote DEUS was that I wanted to understand what’s happening to us, to our culture, our relationship with each other … the essence of humanity, when AI is gobbling up so many of the activities we’ve always thought were uniquely human – creating art, comforting each other. I tried to write it as a journalist, applying journalistic techniques and methods of seeking answers to my questions, but still writing it as fiction – and, as usual, it all got out of hand, and the story took on a life of its own.

My readers are highly interested in Icelandic culture. What other Icelandic authors do you recommend?

I always recommend Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir, whose books have all been translated into English, I think. The Greenhouse and Butterflies in November are some of my favourite novels.

The wonderful Fríða Ísberg is our most prominent young author. The Mark came out in English two years ago, and I’m looking forward to seeing how her second novel, The Hidden Woman, will be received internationally.

There are so many great Icelandic authors I would like to recommend – Andri Snær Magnason, Bergsveinn Birgisson, Ófeigur Sigurðsson, to name but a few – but my most heartfelt recommendation goes to Jón Kalman Stefánsson, of course.

You are bringing Blackout Island to the silver screen. But I have to ask, are you working on a new book?

Yes, the beat goes on! I’m trying to take on the twentieth century, no less! Talk about an age of myths and legends.

What are your favorite places and activities in Iceland?

The West Fiords are the most beautiful place on Earth. They’re off the ring road, the head of the animal that is Iceland on a map, so there are not many tourists there, not even in July. Drive around, take a boat from Ísafjörður to the abandoned Jökulfirðir or the Hornstrandir nature reserve to hike, and your life will never be the same.

My other favourite places are Skagafjörður in the north, which is the place to go horseback riding; the Skaftafell nature reserve in the South-East; and most magical of all, Básar in Þórsmörk in the South, where I try to go every summer to camp and hike.

If you’re based in Reykjavík and don’t have much time to travel around the country,

I recommend the Reykjanes Peninsula to check out the volcanic activity and the rugged nature. There is a small volcano called Búrfell in the outskirts of Reykjavík, with an intact lava channel called Búrfellsgjá – it’s an easy and beautiful hike, where you get a feeling for the volcanic powers at play around the city.

What advice do you have for first-time visitors to Iceland?

Wherever you go, bring your hiking boots and a good jacket, ride a horse, climb a hill, pick the blueberries, and drink water from the tap instead of bottled water. Talk to the locals and ask for recommendations, and try every swimming pool you might find on the way. I’m not talking about the expensive tourist spas and lagoons, although they’re very nice, but no Icelander goes there. We prefer the local pools, which are cheap, lovely, and plentiful all over the country. The water is warm and comfortable, and people bask in the hot tubs all year round, chatting with neighbours, catching up with friends, and arguing about politics. Just shower without your swimsuit before entering the pool, and people will welcome you wholeheartedly.